I re-read A Study in Scartlet recently and have

just finished re-reading The Sign of the Four. These are the first

two Sherlock Holmes novels, published in 1887 and 1890 respectively. But Scarlet is set in 1881 and

many Holmes timelines (which are a source of a lot of speculation among

Holmesians) place Sign of the Four in 1888.

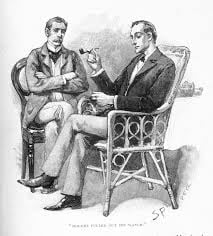

It's interesting to see the differences in Holmes' character between these two novels. In both, he's still a brilliant detective who needs the mental challenge of a difficult case to make him feel truly alive. In Sign, we even see that he sometimes uses cocaine to deal with boredom when he doesn't have something else to occupy his lightning-fast mind.

But there are differences. In the first novel, he's adament about not learning or remembering ANYTHING that doesn't directly relate to his work. If a fact doesn't relate to his chosen profession, he doesn't want to clutter up his mind with it.

But by the time we get to The Sign of the Four, Holmes is able to host a dinner in which he discusses a variety of non-detective related subjects knowledgably. I wonder if perhaps he also came to realize that any piece of knowledge, no matter what the subject, might help him one day solve a case. Or perhaps Watson is having a positive effect on him, turning him in some ways into being a more affable human being.

Here are exerpts from the books that show off this difference in characterization:

FROM A STUDY IN SCARLET:

His ignorance was as remarkable as

his knowledge. Of contemporary literature, philosophy and politics he appeared

to know next to nothing. Upon my quoting Thomas Carlyle, he inquired in the

naivest way who he might be and what he had done. My surprise reached a climax,

however, when I found incidentally that he was ignorant of the Copernican

Theory and of the composition of the Solar System. That any civilized human

being in this nineteenth century should not be aware that the earth travelled

round the sun appeared to be to me such an extraordinary fact that I could

hardly realize it.

“You appear to be astonished,” he said, smiling at my

expression of surprise. “Now that I do know it I shall do my best to forget

it.”

“To forget it!”

“You see,” he explained, “I consider that a man’s brain

originally is like a little empty attic, and you have to stock it with such

furniture as you choose. A fool takes in all the lumber of every sort that he

comes across, so that the knowledge which might be useful to him gets crowded

out, or at best is jumbled up with a lot of other things so that he has a

difficulty in laying his hands upon it. Now the skilful workman is very careful

indeed as to what he takes into his brain-attic. He will have nothing but the

tools which may help him in doing his work, but of these he has a large

assortment, and all in the most perfect order. It is a mistake to think that

that little room has elastic walls and can distend to any extent. Depend upon

it there comes a time when for every addition of knowledge you forget something

that you knew before. It is of the highest importance, therefore, not to have

useless facts elbowing out the useful ones.”

“But the Solar System!” I protested.

“What the deuce is it to me?” he interrupted impatiently;

“you say that we go round the sun. If we went round the moon it would not make

a pennyworth of difference to me or to my work.”

From THE SIGN OF THE FOUR:

Our meal was a merry one. Holmes could talk exceedingly well

when he chose, and that night he did choose. He appeared to be in a state of

nervous exaltation. I have never known him so brilliant. He spoke on a quick

succession of subjects,—on miracle-plays, on mediæval pottery, on Stradivarius

violins, on the Buddhism of Ceylon, and on the war-ships of the

future,—handling each as though he had made a special study of it.

This change in direction for the character is, I think, important. It doesn't seem out-of-character or inconsistant. It simply shows the Great Detective growing a little as a person. Not too much growth, mind you. He's still the Great Detective and will never be --SHOULD never be--a normal human being. But the idea that his friendship with Watson had some effect on him is satisfying. I prefer to think this is the case. After all, we learn in the 1904 short story "The Adventure of the Missing Three-Quarter" that Watson eventually weaned Holmes off drugs. Who knows, maybe encouraging Holmes to occupy his mind with other interests between cases is part of how the good doctor got him to stop shooting up.

While the first attitude makes sense, especially for a one-off character, it is not sustainable in the long run, because a person cannot live long in ignorance of essential facts, especially if one is a master detective. It is more acceptable for Holmes ultimately to be a fountain of knowledge, because any bit of trivia can and does prove valuable to him in later cases.

ReplyDeleteNow whenever I read words of Sherlock Holmes such as those quoted above, in my "mind's ear" (is there such a thing?) I hear the distinctive voice of Basil Rathbone. And of course, Nigel Bruce as Watson. While others have their favorites such as Jeremy Brett, my ideal Holmes will always be Rathbone.

I think you are right on about Holmes' needing to be a fountain of knowledge to also be a master detective. For an in-universe explanation, we can also theorize that Holmes himself realized this after A Study In Scarlett. Perhaps he worked on a case in which some obscure fact was essential and convinced him to expand his fields of knowledge. I still like the idea that his friendship with Watson was a factor as well, though.

DeleteRathbone is a great Holmes. I have always been a little put off when the Universal films moved him into then modern day rather than keep him in Victorian/Edwardian England where he really belongs, but I still enjoy those movies regardless, largely because Rathbone and Bruce are so much fun to watch in those roles.